This year’s edition of ECMWF’s Annual Seminar, which takes place from 1 to 4 September, focuses on physical processes in numerical weather prediction (NWP). Speakers will outline key scientific challenges as well as achievements.

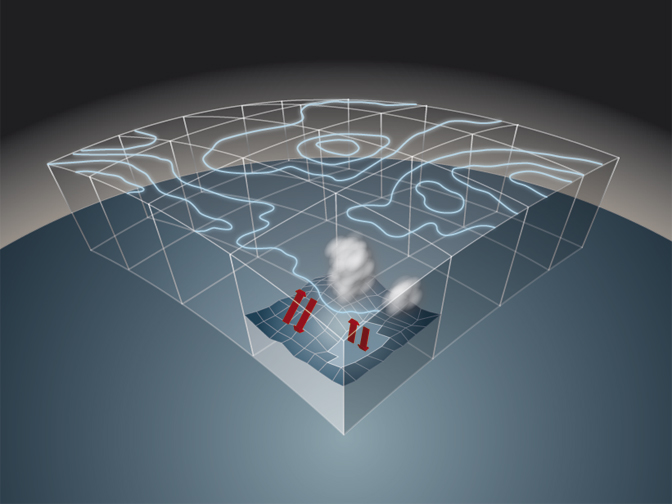

NWP models use the laws of physics to forecast weather parameters such as wind, temperature and moisture. ECMWF’s Integrated Forecasting System can currently predict the values of such parameters at a spatial resolution of about 16 km.

But there are many physical processes relevant to weather forecasting that act at smaller scales. Radiation, cloud formation, convection and turbulence are some examples.

Modelling these processes and their impact on the weather at larger scales can be tricky. Senior ECMWF Scientist Irina Sandu knows a thing or two about that. She gives the example of the drag exerted by the Earth’s surface on air flow.

“Different NWP models use different schemes to represent the drag exerted by the surface, producing very different results,” Irina says. The main reason for this uncertainty is that surface drag is not well constrained by observations.

Irina’s seminar lecture will dissect the impact of the different schemes used to represent surface drag on the performance of NWP models. “In particular, I want to show that orographic drag is handled by a combination of schemes and that models don’t agree on its overall value or even on how the different schemes should contribute to it,” she says.

Resolution challenge

Senior ECMWF Scientist Philippe Lopez will share the story of a major achievement with his audience. It is about how the schemes that handle subgrid-scale physical processes are used in the data assimilation system to help to determine the initial state of the atmosphere, on which forecasts are based.

“The way this is done has been greatly refined over the years, resulting in a better analysis and, ultimately, better forecasts,” Philippe says. In his lecture, he will present the results of experiments that prove his point.

But there is a challenge on the horizon. The data assimilation system used at ECMWF to determine the initial state requires linear versions of the physics schemes to be used. That works well at current resolutions but may become more difficult as the spatial resolution of the forecasting model increases.

“With increased resolution, there are more and more issues to be resolved. In the future we may not be able to make the linearization work in the same way as we do now,” Philippe warns.

And the challenges brought by resolution upgrades do not end there. In the coming years, ECMWF is expected to run resolutions where some physical processes are partially resolved. “Scale-aware schemes are needed and will require substantial effort,” says Anton Beljaars, the Head of the Physical Aspects Section at ECMWF, who will deliver the seminar’s introductory lecture.

Peter Bechtold, the Head of ECMWF’s Moist Physics and Radiation Group, gives the example of convection. “The way to represent convection beyond resolutions of 8 or 10 km is the subject of considerable debate in the community. Presenting our simple strategy and preliminary results should contribute to a lively discussion,” he says.

Peter, Anton, Philippe and Irina are just four of the 28 scientists from half a dozen countries to speak at the seminar. Their lectures will cover the role of different physical processes in the atmosphere and the way they are represented in forecasting models. Additional topics are the role of physical processes in data assimilation, verification, and the representation of model uncertainty in ensemble systems.

For more information, please visit our 2015 Annual Seminar page.