Weak El Niño conditions observed since October 2014 are expected to strengthen over the next few months and may turn into a substantial event, but there is a great deal of uncertainty beyond June 2015, current forecasts suggest.

An El Niño event is a prolonged period of abnormally high sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean. It goes hand in hand with changes in atmospheric conditions and can have strong repercussions on global weather patterns. El Niño can also significantly affect the global average temperature and hence influence the global warming signal.

“The latest ECMWF seasonal forecast from 1st March 2015 shows that in the coming months the equatorial Pacific surface temperature is expected to rise further, giving a moderate strengthening of El Niño conditions,” said Tim Stockdale, the head of ECMWF’s Seasonal and Long-Range Forecasting Group.

“After June, the uncertainty becomes large: in some ensemble members El Niño conditions start to dissipate, in others the event remains large or even amplifies further. As always in El Niño forecasting, the eventual outcome will depend very much on how strongly the winds respond to the warming sea surface temperatures,” he added.

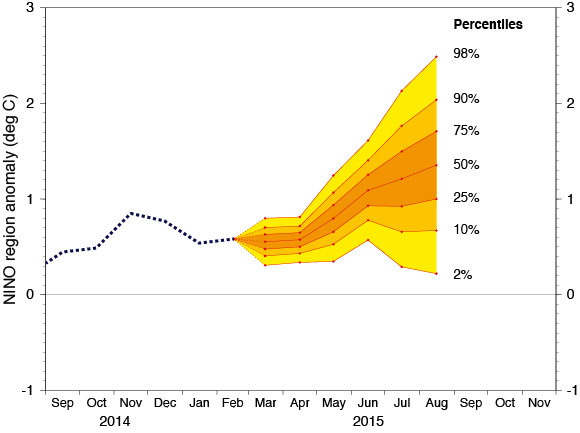

Ensemble forecasts account for the uncertainties inherent in the prediction of weather and ocean parameters by producing a whole set of possible outcomes. Figure 1 shows the spread of ensemble members in the EUROSIP multi-model seasonal prediction for El Niño produced on 1 March 2015.

Figure 1 The spread of high-probability outcomes widens significantly after June 2015

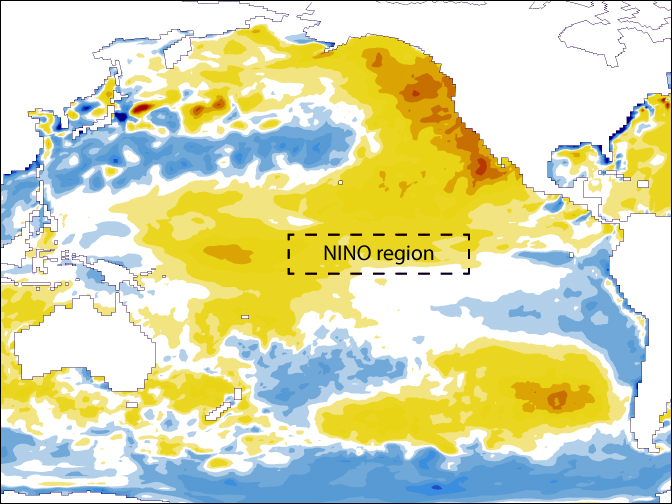

The standard El Niño index is the average sea surface temperature anomaly over the NINO region in the central-eastern equatorial Pacific, shown in the top image.

The EUROSIP probability spread of sea surface temperature anomalies is calculated from the ensembles provided by four different forecasting centres: ECMWF, the UK Met Office, Météo-France and the US National Centers for Environmental Prediction. It suggests that there is approximately a 75% chance that sea surface temperature anomalies will exceed 1 degree Celsius by August. Conversely, there is a 25% chance that they will not.

The uncertainty in the development of the current El Niño conditions has prompted the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) to be cautious. “While current forecasts imply that a careful watch must be kept on the tropical Pacific Ocean temperatures, it is too early to assess the strength of any potential event,” the WMO’s latest El Niño update says.

An “exceptional” El Niño in 1997

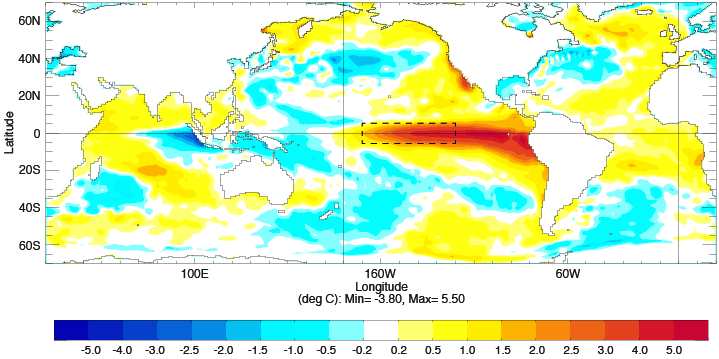

Notably, current ocean conditions have a weaker signal than those that preceded an event in 1997, when a combination of a large ocean signal and strong westerly winds led to an "El Niño of the century". Figure 2 shows the sea surface temperature anomaly in the tropical Pacific region at its peak, in November 1997.

Figure 2 The sea surface temperature anomaly peaked in November 1997

The El Niño of 1997 coincided with the start of experimental real-time seasonal forecasting at ECMWF. The success in predicting both the El Niño and its global impacts helped raise the profile of seasonal forecasting at ECMWF.

In December 1997, at the height of the El Niño event, ECMWF began publishing seasonal predictions on its website. The text accompanying the products explained that, “taking into account the exceptional El Nino event of 1997, and following overarching WMO requirements, the ECMWF Council has decided to make a range of products from the experimental programme of seasonal prediction available on this site."

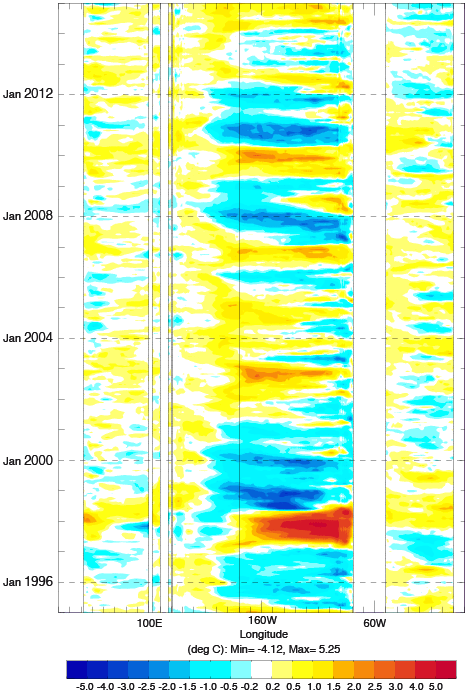

Since 1997, there have been a number of weaker El Niño events. This is reflected in Figure 3, which shows the evolution of sea surface temperature anomalies from 1996 to the present, with a conspicuous spike in 1997-98.

Figure 3 Observed sea surface temperature anomalies at the equator, 1996 to the present

The chart shows more or less regular fluctuations between warm El Niño conditions and colder episodes in the central and eastern Pacific, dubbed La Niña. Time will tell what the top of the chart will look like by the end of 2015.