Louise Arnal, PhD student at ECMWF and the University of Reading

I’m a scientist by training and am now studying for a PhD at ECMWF and the University of Reading on European seasonal hydro-meteorological forecasting. But coming from a family of artists, art has always been a part of my life and I love it! Just over a year ago I began to explore how I might combine art and science in my research.

Why combine art and science?

Modern day science would not exist as it is without art. And modern day art would not exist as it is without science. In fact, the distinction between science and art is relatively recent. Until the 17th century, art was used to refer to a skill or mastery, and was not differentiated from science. During the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci was using science to elevate his art, fusing both disciplines to question the world in which he lived.

Today, science is about putting two and two together, connecting dots to seek an objective answer. Art appears to differ fundamentally from science, stimulating senses, imagination and emotions. Behind these apparent dissimilarities hides a fruitful complementarity.

Back in the early 20th century, for example, L. C. W. Bonacina believed that the close relationship between aesthetic and scientific problems was vital in reaching a unifying vision of our world. He argued that the description of meteorological events could not be done by numerical measurement and verbal categorisation alone, but needed to be completed by pictorial qualification. The contemplation of beautiful scenes can, for example, raise novel scientific questions, while scientific knowledge can enhance aesthetic appreciation.

The classification of clouds as we know it today would not have been possible without the fruitful combination of science and art1. Before the 19th century, meteorologists thought each cloud to be unique in every way. We had to wait until 1802 for Luke Howard, amateur meteorologist, to put forward the now widely used clouds classification. Luke Howard spent years monitoring the skies and making sketches and watercolour paintings of clouds from which he came up with the three beautifully descriptive Latin terms: cirrus (a curl of hair), cumulus (a heap), and stratus (layer). Science and art historians also believe Howard’s scientific classification of clouds has influenced artists throughout Europe, such as painters John Constable and Joseph M. W. Turner, changing the way clouds were depicted in many 19th century European paintings compared to earlier work.

A cloud study of cumulus and nimbus rainfall by Luke Howard (c1803-1811). (© Royal Meteorological Society)

Science and art today

Science and art collaborations have soared in the last few decades, with the term SciArt coined to describe this rising phenomenon. There are nowadays many SciArt projects on the topic of weather and water. I would like to use this post to talk about a few pieces which have inspired me.

UK-based artists Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway created an art installation called Most Blue Skies. As part of this installation, a computer runs continuously to find “the bluest skies” in the world, by measuring the passage of light through particulate matter in the atmosphere and calculating the exact colours of the sky at billions of places on Earth. By combining “atmospheric research, environmental monitoring and sensing technologies with the romantic history of the blue sky and its fragile optimism”, this project looks at “our changing relationship to the sky space as the subject for scientific and symbolic representation”.

Climate change is a topic that has been widely explored with SciArt by both scientists and artists. One piece that I particularly like is the work of visual artist Andreco for the Climate 04-Sea Level Rise project. Inspired by international research about the effects of sea level rise and extreme waves in the Venice lagoon, Andreco made a big wall painting in Venice to bring these scientific concepts and motivations to a broader audience and stimulate public discussions on the causes and effects of climate change.

Andreco working on his wall painting in Venice in 2017. (Photo: Andreco - CLIMATE 04 - Sea Level Rise - Venice - Photo: Like Agency - www.climateartproject.com)

Science and art is also becoming more present amongst scientific institutes and at scientific conferences. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) has been hosting a SciArt summer school for the past few years, followed by the Resonances festival where the co-created work of artists, the JRC and invited scientists is presented to stimulate conversation on a chosen topic. You can read about my impressions from this year’s summer school on Big Data. Art is also becoming more present at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) General Assembly, where a SciArt session has been held for the past couple of years for scientists and artists to show their SciArt work on any environmental topic. This year for the first time, the EGU also hosted two artists in residence at the General Assembly.

My SciArt journey

I have worked on a series of SciArt projects, which you can read about on my blog.

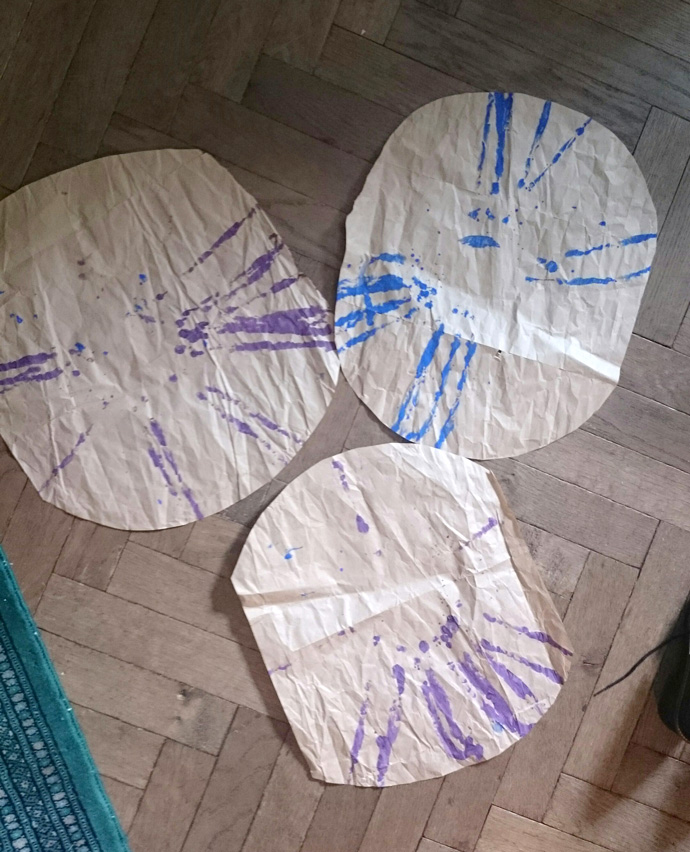

One topic that particularly interests me is that of chaos or randomness. It is intrinsic to weather forecasting and can be explored in so many different ways using art. I recently explored this by repeatedly dropping a ball (full of paint) on nails of random heights. The ball leaves a set of random traces of paint on the paper. This is just like the “butterfly effect” in weather forecasting. Small changes in the model’s starting conditions (the initial states of the atmosphere, ocean and land – here the nails of random heights) can lead to very different outcomes (or weather forecasts – here the traces of paint left by the ball).

Chaos experiment results by Louise Arnal (2018).

I am currently working on a SciArt installation for my PhD, on the topic of seasonal flood forecasting. I am also collaborating on a SciArt project on the visualisation of natural phenomena in higher dimensional space. Led by scientist and artist Renate Quehenberger, it will be displayed during the 2019 Resonances festival.

Art is much more than a tool to communicate science. Art and science are two different tools to explore and communicate a topic, and used in parallel, can initiate a dialogue between scientists, artists, and the public.

1 https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/the-man-who-named-the-clouds/ and https://hyperallergic.com/261023/how-the-naming-of-clouds-changed-the-skies-of-art/