ECMWF Director of Forecasts Florian Pappenberger and the Deputy Director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) run by ECMWF, Samantha Burgess.

Europe has seen several heatwaves since June, during which several records were broken. ECMWF Directors point out that these were the result of different meteorological conditions, and that climate change plays a role in their impacts.

Different types of heatwaves

“Heatwaves lasting around one to three days can be due to the transport of warm air from lower latitudes, in the case of Europe often from the Sahara, together with local heating from solar radiation,” says Florian Pappenberger, Director of Forecasts at ECMWF.

The heat that affected parts of western Europe in mid-July was partially caused by this phenomenon. A new record temperature of 40.3°C was reached in the UK, exceeding the previous record by 1.5°C. Temperatures also exceeded 40°C in France, 45°C in Spain and 46°C in Portugal.

“Alternatively, heatwaves can be the result of a stationary high-pressure system with clear skies and weak winds. These conditions can create longer heatwaves, such as the recent one in mid-August,” Florian adds.

“The effect on near-surface temperature depends on how much energy is used to evaporate water from the ground and plants, and how much is heating the air. If the soil is already dry or the surface is just concrete and tarmac, there is little cooling of the near-surface temperature due to evaporation. Instead, most of the energy will heat the air and thus increase the magnitude of the heatwave.”

There is, however, no standardised definition of a heatwave. The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) has recently said that a heatwave is “a period of statistically unusual hot weather persisting for a number of days and nights”.

The influence of climate change

The heat this summer raises the question whether climate change is responsible.

“The series of European heatwaves this summer were caused by particular weather patterns, but the temperatures experienced were hotter than they would have been because of climate change,” says Samantha Burgess, the Deputy Director of the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) run by ECMWF. “As the climate warms, Europe will experience more frequent and more intense heatwaves.”

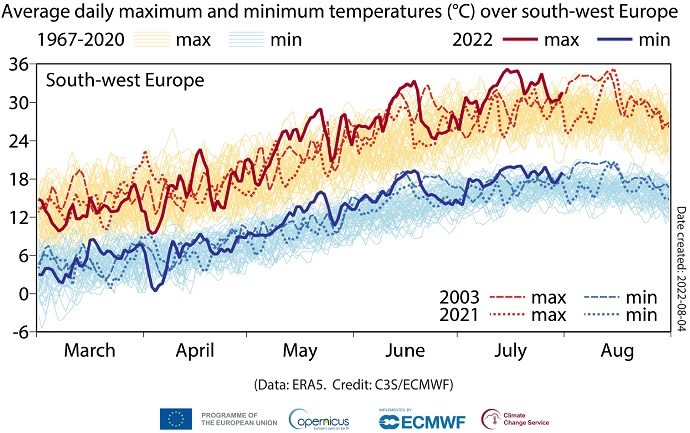

A chart covering southwestern Europe highlights three years, 2003, 2021 and 2022, during which maximum average temperatures were reached.

Daily maximum and minimum temperatures (March–August) averaged over southwestern Europe. Source: C3S/ECMWF.

“Climate change makes very high temperatures much more likely, as has been shown specifically for the UK,” Samantha said.

For example, without climate change temperatures above 40°C in the UK would have been extremely unlikely, the WMO said with reference to a World Weather Attribution analysis.

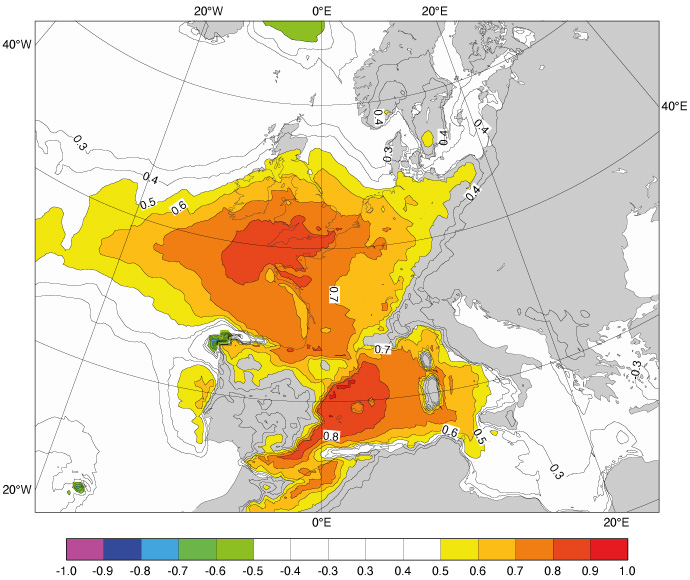

Daily surface air temperature anomaly for July 2022 relative to the daily average for the period 1991–2020. Data source: ERA5. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service/ECMWF

The link with droughts

Heatwaves can cause droughts, but droughts also occur without a heatwave.

“A long heatwave will result in a drought due to the lack of rain and enhanced evaporation due to the high temperatures,” Florian says.

“Droughts will also increase the temperature during heatwaves due to a lack of moisture in the soil, causing less evaporation from plants. However, there can be droughts without a heatwave and a heatwave without a drought.”

The range at which ECMWF predicts heatwaves

ECMWF specialises in global medium-range forecasts, in other words from three to ten days.

“In the medium range, we have provided skilful predictions of heatwaves more than a week in advance,” Florian says.

This chart aims to provide pointers to areas where anomalous values of 2 m temperature are likely to occur based on the ECMWF ensemble forecast (ENS) system. It shows the Extreme Forecast Index (shading) for 11 to 14 August 2022 in a forecast from 5 August 2022.

“Especially in the first few days of a forecast, there is a challenge in capturing the magnitude of temperatures. For example, our Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) does not yet represent built-up areas. We should thus expect the model to underestimate temperatures for large airports and cities.”

ECMWF also covers the extended range, up to 42 days ahead, and the long range, up to 13 months ahead. “In the extended range we have seen some early signals for warmer temperatures than normal,” Florian says.

“Future improvements of the land surface model, including cities, are expected to provide a more accurate coupling between the atmosphere and the surface in terms of energy exchange. They should help to better capture the magnitude of heatwaves.”

Many of ECMWF’s latest forecasts are publicly available in the Open Charts catalogue.

Heatwaves in C3S

The C3S service provides both monthly summaries of climate-related data and news articles on particular developments, such as the European heatwave in July this year. In addition, C3S produces a yearly summary of the European State of the Climate.

“These products can be used to track the climate and how it changes,” Samantha points out. “They show, for example, that the hottest summer in Europe was in 2021, yet 2020 was a warmer year overall.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says in its sixth assessment report that the “frequency and intensity of hot extremes will continue to increase” even if global warming is stabilised at 1.5°C.